Hot on the heels of part 3, here is the next part of my study. In part 4, I look at the post-study abroad experience. This section uses a number of quotes from respondents, which I think complement the graphs/tables well, and deepen our understanding of the individual experience and impact. Let me know what you think!

Post-study abroad impact and decision-making

Of the 103 respondents, 44 were still studying and were therefore only able to provide limited responses to questions about how study abroad had changed them. Of the remaining 59, 42 were in employment, 12 had started a new course of study, 3 were full-time parents and 2 were looking for work.

Employment prospects

The employment rate of 95% amongst completed students compares very favourably to the general employment rate in Tajikistan, which is unofficially estimated to be around 60% (Asian Development Bank, November 2010)[1]. Three employment sectors were identified from those in employment, where this was stated in the response:

- Nearly half work for some form of international organisation, with the UN system featuring prominently;

- Just under a third work in the private sector such as banking, logistics and consultancy;

- Around 15% teach or research at a school or university.

A rare report on higher education in Tajikistan suggests this is to be expected: ‘graduates/alumni of the international scholarships programmes or universities, the most talented youth, prefer to find work with international organisations or in the private sector’ (National Tempus Office Tajikistan, October 2010, p8). There also appears to be a match between the subject studied (see figure 6) and the career fields students are progressing in, reinforcing the strong inclination shown by respondents to study abroad in order to improve their career prospects.

Interestingly, respondents’ attitudes to their time abroad varied by the career sector they now worked in. Those working in the private sector were less positive about the impact of study abroad on their career prospects, as this sample response shows:

“I am working in Tajikistan now. I am an entrepreneur. To be honest I expected that studying abroad would help more with finding a good job. But so far it has turned out that it was not as helpful as I thought it would be.” – male, 24

On the other hand, respondents who said they were working for an NGO or in academia/teaching assigned greater value to their study abroad:

“I work as a development specialist at the United Nations. My studies definitely enabled me to take this path.” – female, 29

“Now I am teaching secondary level students about Islam as a civilization in Khorog, Tajikistan. Studying abroad helps me a lot with this. For instance, I am able to use various methods of teaching; I know how to manage my classes better and effectively; I know various ways of approaching my students of different academic achievements; I know how to better and effectively approach my students’ parents and involve them in their learning process.” – male, age not stated

Where are they now?

Respondents in employment showed the highest tendency to return to Tajikistan. Whilst a quarter of those in employment did not state which country they were working in, of the remaining number, there was an almost equal split between those who had returned to Tajikistan (16) and the number who had stayed abroad (15). Of those who stayed abroad, the two biggest destination countries were the UK and the USA with 20% of respondents each, and the remaining 60% scattered across the world – from Uruguay to Ethiopia to Thailand. This result was surprising as a popular perception in Tajikistan is that once an individual has the opportunity to go abroad, they are likely to stay abroad to continue pursuing better opportunities.

For respondents doing a new course of study (12), only 2 were doing so in Tajikistan. 6 were in the USA and 4 did not state their destination. Of the three full-time parents, 2 were in European countries and 1 did not state their destination. And both of the respondents currently looking for work were doing so in the USA.

Overall, therefore, 31% of respondents were back in Tajikistan compared to 44% who were out of the country (25% did not state their location). It is not known whether those who remained out of Tajikistan planned to migrate on a permanent basis, although two respondents noted that they lived abroad permanently due to marrying someone from a different country. White and Ryan suggest that the networks built by migrants whilst abroad ‘are increasingly important to understanding patterns of migration’, and strong networks built up within the receiving country can facilitate the chances that migration becomes long term or permanent (2008). It would be interesting to track the students who stayed abroad on a longer term basis to investigate the extent to which study abroad is a form of temporary, rather than permanent, migration and how the networks students construct influence the length of the period abroad.

Impact on family/friends

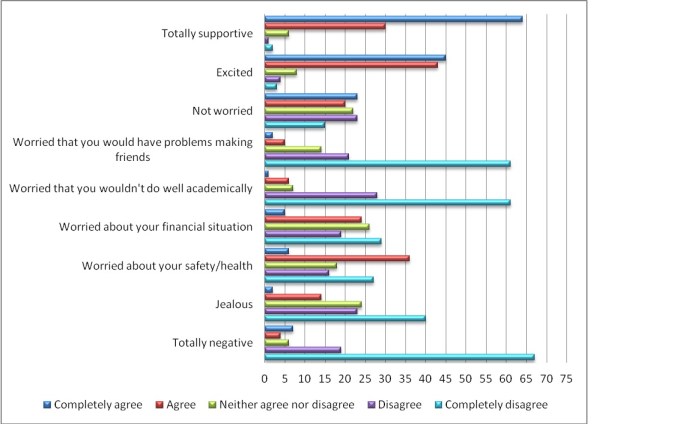

Respondents were asked two questions about the opinions of their family and friends. The first question, shown in figure 10, used a Likert scale to assess how family and friends felt about the decision that respondents had made to study abroad and suggest that the reaction of family and friends was overwhelmingly positive. Three answers generated a much more mixed range of responses: ‘worried about your financial situation’, ‘worried about your safety/health, and ‘not worried’, demonstrating that whilst overall family and friends were likely to be very supportive of the decision to study abroad, this did not prevent them from harbouring concerns about aspects of the student’s personal well-being. Concerns about academic progress (‘worried that you wouldn’t do well academically’) were minimal, indicating that family and friends had confidence that by deciding to study abroad, the student was in effect already demonstrating a high level of academic ability.

The second question was free text and asked respondents to state what their family and friends thought of their decision to study abroad now, i.e. at the point they had either already started or completed their studies. Almost every single respondent reported supportive reactions:

“My family and friends think my decision was the best one and if I stayed here in Tajikistan then I would never [have] been able to achieve what I have achieved so far. Now my parents think that I should go on to [do a] PhD and finish up what I have started.” – male, 25

“I worked hard to study abroad because of my family. They always were supportive.” – female, 29

The strong positivity demonstrated in figure 10 has therefore for the most part been sustained and responses showed that some families and friends had become more encouraging in their attitudes. As one respondent put it:

“I am proud that my family walk with high heads because of me” – female, 29

For a small minority, however, the reaction of their family and friends is mixed, or negative:

“My family and friends are happy that I am studying and living abroad now. My parents, though, sometimes ask me to come back as they don’t want their children to live in any other country for a long period of time.” – male, 34

“My family was against my study abroad since [the] beginning and has not changed their view. My friends were neutral and do not share their view.” – female, 36

It is worth noting that family relationships in Tajikistan and other Central Asian countries are distinctive from European/American models. For example, people generally marry earlier and have more children, although this pattern is changing. Further, it is common for elders to have more control over family life and decisions, and for family life to be more intergenerational (Roberts, 2010). This may help to understand the reticence communicated by a small number of respondents.

Impact on self

The final question in the survey asked respondents to comment on how they have changed as a result of studying abroad, the aim being to understand the extent to which study abroad affects levels of well-being. The majority of respondents asserted that they had changed in at least one of the categories employed in this paper to describe change (cross-intercultural experiences, human development, intellectual development), as shown in figure 11.

In terms of cross-intercultural experiences, Opper et al note that study abroad ‘provides a direct opportunity for cultural learning through the broadening of knowledge and views internationally… an understanding of other cultures stimulates, in turn, some reflection about one’s own culture, and even a reconsideration of values in general, apart from application to any specific country’ (1990). The responses in the survey can be grouped into two types. Firstly, some respondents noted that their views of Tajikistan had changed, either positively or negatively:

“I used to idealize foreign specialists before going abroad myself… Today, however, after having studied so many years abroad, I think that Tajik specialists and professionals are highly underestimated and underpaid.” – female, 31

“[I] didn’t like Tajikistan before but [I] hate being there now. I would never go there if not for my family and friends.” – female, 41 or above

The second type of response commented on their changed views of other countries and cultures:

“I am no longer in love with the West. The more I studied here the more I understood the working of a neo-colonial system and how the richness of the West is built up on [the] backs of developing countries. I guess I no longer see the West or democracy as something that will ‘help’ Tajikistan.” – female, 30

“The knowledge and experience of studying and living in the UK… will certainly have an impact on [a] person’s life and worldview…. all these studies and experiences at leading universities in the UK has changed my view about the world and Tajikistan…” – male, 38

Respondents reporting human development-related impact focused on improvements to their skills: those related to their personality (e.g. increased confidence and responsibility) and skills that would enable them to improve their career prospects:

“[I] became more tolerant and open, more self confident, improved my academic background, and being a student here I already have 2 job offers with a good salary back in Dushanbe [capital of Tajikistan]” – female, 23

“I became more independent and responsible as I thought I would be. And I feel I am ready to move on, starting with exchange programs, internships abroad, meeting more people, using any work (career) opportunities.” – female, 18

Intellectual development connects primarily to reported improvements in academic knowledge and skills, but a number of respondents also directly related this to how they perceived their responsibility to make changes in Tajikistan:

“The primary change in me personally is my academic ability, questioning various subjects across disciplines” – male, 31

“It is obvious that after studying abroad your attitude to your country changes totally. Now you begin to look at your country with the question “how I can contribute to the development of Tajikistan” and you begin to realize that the future of your country is your hands.” – female, 23

It is evident that all respondents had changed in at least some way as a result of studying abroad. At its deepest, studying abroad can be ‘a profound transformational experience’ (Gu, 29.01.2012) and many of the respondents said they had changed greatly across the three categories used in the paper:

“I am so much [a] different person now than I was back then. Education here has broadened my mind to the things that I had no idea of their existence and as I grow in possessing my knowledge I see the opportunities that I can get, and the things that I can do in my life and with my life. I am [a] much happier person now than I was before.” – female, 26

[1] It should be noted that the official unemployment rate is 2.2% but most indicators suggest that this is based on incomplete criteria and therefore does not capture the full scenario.

Leave a comment